A Narrative Detail of My Third Iteration

- jaj160

- Nov 13, 2021

- 11 min read

Updated: Nov 14, 2021

"To depict a donut, it is virtually impossible to avoid a two or three-dimensional ring shape in some shade of brown, unless depicting a filled donut or a bear claw. Further, although not all donuts are frosted, strawberry pink is an exceedingly common and popular choice for frosting, and as a result has become a standard choice for depicting a donut."

U.S. Copyright Office Review Board, March 21, 2019.

Hello friends,

I have been writing for days, beginning with the apparently naive expectation that I could recount the progress made in my third iteration both in MS Word format (as in, like a proper paper) and in a manner that would be brief. I was wrong.

I undertook to write my third iteration "like a proper paper" because I will need to leverage this work in at least one but ideally two formal contexts: first (and certain), as a contribution to my Preliminary Examination Portfolio and second (less certain, but hopeful and dare I say, likely) as a conference submission later this winter. I don't think that will work for our more collegial review needs in DSAM 3000, so I am writing a less formal narrative detail here.

As you might recall, I set out to test my thesis that digital tools could help users ascertain values embedded in copyright law. Specifically, I set out to apply a particular digital tool - topic modeling to a corpus of rejection letters downloaded from an online database of final decision letters written by the Review Board of the US Copyright Office to entities - mostly people but sometimes organizations - who have appealed prior rejections of their applications for copyright protection in submitted works. The topic modeling tool was MALLET, a program developed by Andrew McCallum at the University of Massachusetts - Amherst.

My prior iteration of this project was dominated by technical struggles. It was quite difficult for me at first to install MALLET and similarly difficult to convert the downloaded pdf files to the plain text files required by MALLET. I was making these conversions one-by-one using Adobe Acrobat, a process that was sufficiently slow as to limit the corpus of data that I was able to analyze to include only 43 letters. This did not prove to be a sufficient amount of data for the statistics underlying MALLET's topic modeling computations to return meaningful results.

You may recall that I ran three initial runs as part of my prior iteration, requesting sets of three, five and ten topics from MALLET. The results I got were as follows, peppered with words that felt intuitively "right" but also with product names and other overly-specific terms that made the whole lot feel intuitively "wrong":

Three Topics

Five Topics

Ten Topics

Due to conversations with Alison and Tyrica Terry Kapral - Hillman Library's Humanities Data Librarian - I got the sense that what was returned by MALLET in my initial run was compromised by the relatively small number of documents contained within my corpus so my first step in undertaking my third iteration was to return to the Review Board's database and download all of the rejection letters - a set that numbered just over 200.

Working with Ms. Terry Kapral and aided tremendously by some Python scripts that she provided to me, I was able to almost instantly convert all 200+ pdfs into .txt and just as quickly, trim away the formulaic text that comprised the letters' introductions and conclusions (as well as a handful of other sections), remove encoded formatting like line breaks and lemmatize words down to their roots. For reasons not understood by me, about thirty pdfs remained impervious to Ms. Terry Kapral's code; what remained was a set of 176 .txt files that were in very good shape and ready to be run through MALLET. These became the corpus that was analyzed by MALLET in this iteration.

In running this analysis, I added a stop words list to the one that is programmed into MALLET such that I was able to exclude most numerals. I then ran the program three times, requesting a set of three and then five and then ten topics. The results I received were as follows:

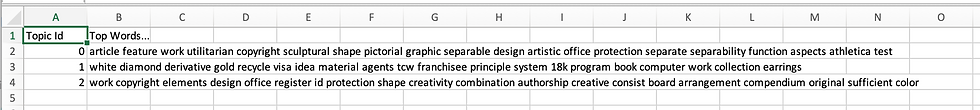

Three Topics

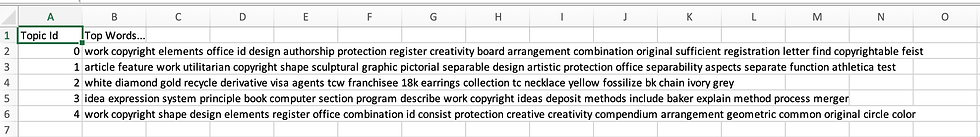

Five Topics

Ten Topics

Looking at these, I felt much more confident that my dataset had been improved to the point that the topic models generated did in fact suggest some meaningful insights. Considering the three sets that I had generated, I chose to work with the set of five topics, as I found that set to strike a good balance been too general (as struck me as the case with the set of three) and too specific (as struck me as the case with the set of ten). I determined then that given that the "run of five," as I came to think of it, resulted in a reasonably strong set of topics, I was in a good place to begin investigations into those topics.

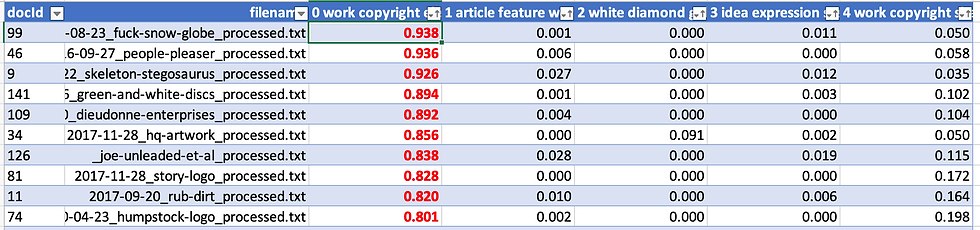

When generating a list of topics, MALLET returns the topics as well as a host of other information arrayed across a small collection of individual files. It produces those files in .html and .csv formats - the data is identical between the two, but just displayed differently. To begin my analysis of "run of five," I reviewed the .csv files and determined that one - "topics-metadata" was particularly useful for my interests. It assigns a row to each file that comprised my corpus (so, one line per every converted, trimmed and lemmatized rejection letter) and then displays the proportion of words in that file that are tagged in association with the terms in each of the five topics. What results is a spreadsheet file that when sorted correctly can reveal which topics are most strongly represented across my corpus as well as which individual documents contain the highest proportion of words associated with each topic.

The above is a screenshot of the topics-metadata file associated with my "run of five". As you can see, I converted the text to a table and applied some simple sorting and conditional formatting to "sift" the documents most strongly associated with individual topics to the top of the respective rows.

This sorting and formatting allowed me identify that, in descending order, the most strongly represented topics across my documents are (here represented by the number id assigned to them by MALLET, as well as by the top 20 words that comprise them):

4 – work, copyright, shape, design, elements, register, office, combination, id, consist, protection, creative, creativity, compendium, arrangement, geometric, common, original, circle, color

0 – work, copyright, elements, office, id, design, authorship, protection, register creativity, board, arrangement, combination, original, sufficient, registration, letter, find, copyrightable, feist

1 – article, feature, work, utilitarian, copyright, shape, sculptural, graphic, pictorial, separable, design, artistic, protection, office, separability, aspects, separate, function, athletica, test

2 – white, diamond, gold, recycle, derivative, visa, agents, tcw, franchisee, 18k, earrings, collection, tc, necklace, yellow, fossilize, bk, chain, ivory, grey

3 – idea, expression, system, principle, book, computer, section, program, describe, work, copyright, ideas, deposit, methods, include, baker, explain, method, process, merger

In this iteration of our projects we have been asked to reflect upon whether our original thesis is supported or refuted by our work thus far. Interestingly, and perhaps in keeping with the legal nature of my subject material, my answer is that "it depends". It depends largely on how I define the many vague terms that comprise my thesis and it depends on how one defines the results of my work. If the topics listed above are considered to be the findings that will either support or refute my thesis and if the "users" mentioned in my thesis are unfamiliar with copyright law, I would say that my results are likely to refute my thesis. What "values" might be discerned from the above topics are likely to include originality, creativity and utility. To determine that these are values embedded in copyright law would be to be right in some regards (original and creative works are good fits for copyright protection), wrong in others (useful objects are not) and effectively too vague in the determination to result in any insight (creative components of useful objects can be. It depends). To draw an accurate conclusion, one would need to have a relatively well-informed understanding of the law.

At this stage in my work, I do not consider the topics generated by MALLET to be the evidence that will either support or refute my thesis because I don't consider them to be the evidence compiled by my investigation. As someone who knows a relatively good bit about copyright law, I could immediately ascertain from the words associated with the topics that they were hinting at something rather than telling me something. It was as if I was on a beach with a metal detector: it was sounding loudly in particular directions and oddly suggestive in others. I knew I had to dig to find the goods, though. This is to say that to find evidence in support or refutation of my thesis, I had to read the letters themselves. I knew this because I knew what I was looking for.

To select the best letters to read, I used my topics-metadata file to identify the documents that were most strongly associated with each topic and working topic by topic, I read them all. As mentioned, I felt going in that my proverbial metal detector was beeping very loudly when it came to certain concepts and even, yes, certain values. For instance, I was able to determine by reading the top ten documents representing each that Topic 4 was indeed a topic "about" geometric shapes. Effectively, and on their own, geometric shapes don't qualify for copyright protection because they aren't sufficiently creative or original. To read a good explanation of the law and how a work might fail to meet the necessary standards here, I invite you to peruse the letter below pertaining to the Fuck Snow snow globe. It is provides an excellent introduction to the interplay between geometric shapes and creativity, and is a hilarious read (as many of the rejection letters are).

Likewise, by reading the top 10 documents associated with Topic 1, I was able to confirm that the works they addressed were useful objects, a category of creations to which copyright protection is uncomfortably applied. A useful object is not itself subject to the provisions of copyright law, but creative works are. A creative component of a useful object can be protected by copyright provided it can be separated from the useful component of the work and still retain its integrity as a creative work. This is why the terms "separable" and "separate" feature in Topic 1. For another insightful and very funny rejection letter this time related to the matters of utility and separability, I refer you to the letter below pertinent to the Toy Donut Pointer.

My conclusion thus far is that my thesis wasn't well defined enough to lead to a confirmation or refutation. However, if one can define "digital tools" as, in this case, topic modeling (and more specifically, MALLET); "users" as users familiar with copyright law; and "help ascertain" as "point in the right direction" then, sure, my thesis is supported by my evidence thus far.

Regardless, I don't think that is the interesting story told by the topics identified in my data. What emerges most clearly for me from my corpus of letters and my analysis of the "topics" that MALLET identified is that what they suggest has little to do with values and instead much more to do with a lack of civic understanding about the varying types of intellectual property protection available to works and their creators. Had some applicants applied to different offices for different kinds of intellectual property protection - namely, trademark and patent - they could well have been more successful. That it is copyright protection that seems to have captured their attention and unrequited affection is itself very interesting, and also suggestive of certain values.

Rather than speculate about these right now, I will direct my attention instead to some of the specific prompts that we have been asked to address in our narrative account of this iteration. Many of these pertain to our Mindful Practice Journal, which I refer to as my MPJ. Honestly, my MPJ entries became fairly slim over the course of this iteration, likely because I became less uncomfortable. As my skills and my familiarity increased, I forgot that I was supposed to be mindfully self-conscious. This said, I did remark multiple times at the start of this iteration at just how much explicit and explicitly human effort was required of my digital humanities undertaking. At one point, I had involved two professors and a librarian, directly involving four humans (and indirectly involving the many others who wrote the programs we were using) in what at the start of this semester I would probably have called "computer stuff".

Additionally, I never did directly write as such in my MPJ, but reflecting back on what notes I did make, I can see that my thinking was beginning to shift from a consideration of values embedded in text to the value of textual clues as might be provided by an approach such as topic modeling. Informally, I used the topics generated by my run of MALLET to engage my boyfriend and my sister in conversations about copyright law and was able to teach them about the law in ways that I was never able to communicate well prior. I was able to see a substrate of meaning criss-crossing documents that previously I'm not sure I would have been able to cross-reference so generatively. It was fascinating. In "Words Alone: Dismantling Topic Models in the Humanities", Ben Schmidt writes of topic modeling as having "no business" being as accurate as he found it to be. I found myself with similar sentiments - how in god's name did MALLET "know" to find a relationship between ideas, systems and programs as it did in Topic 3? It makes brilliant sense, and illuminates so much.

However, it only does so because I know what I'm looking for.

One of the prompts that we have been asked to address in this iteration regards the feedback that we have received thus far. One of Alison's regarded how I felt I knew what I knew when analyzing the initial set of returns suggested by MALLET as part of my second iteration. If you'll recall, I've stated that I knew intuitively that they were off the mark, due in part because of their over specificity. The more direct explanation, however, is that I knew they were not quite right because I knew what I was looking for. It is for this same reason that when I considered the results from this iteration's run, I knew they were "right". It was my prior understanding of copyright law that allowed me to read collections of words such as "geometric, shape and elements", "arrangement, combination and original" and "utilitarian, sculptural and separability" and know

This is why I am increasingly of the opinion that topic modeling might be a great teaching tool, and why I am also increasingly able to see its value as an indexing tool. This was its original purpose, and it is fascinating to me that I have been able to see evidence of its value in this regard as I have worked with it.

Looking forward to the fourth and final iteration of this project, it is my goal to distill all of this more concisely and to be able to report more insightfully on the two topics - Topics 2 and 3 - that make intuitively sense to me but that I have yet to accurately "diagnose". If time permits, I would also like to engage Tyrica Terry Kapral's expertise just a bit more and work, if she is willing, with my corpus in Voyant. What MALLET does with words Voyant is able to visualize with graphics - or at least in a sense. If I have time, I would like to explore this tool a little further so that I might understand it better and potentially gain some insights from it into the corpus I've been working with.

This has been a fascinating project, and one that has been far more informative than I would have imagined. I look forward to continuing to explore my way through it, and I thank you in advance and as always for your generous feedback.

Fuck Snow Snow Globe Rejection Letter

Toy Donut Pointer Rejection Letter

My Current Dataset

My Complete 5-Topic MALLET Results

Comments